Chiesa di San Salvatore

San Salvatore Church

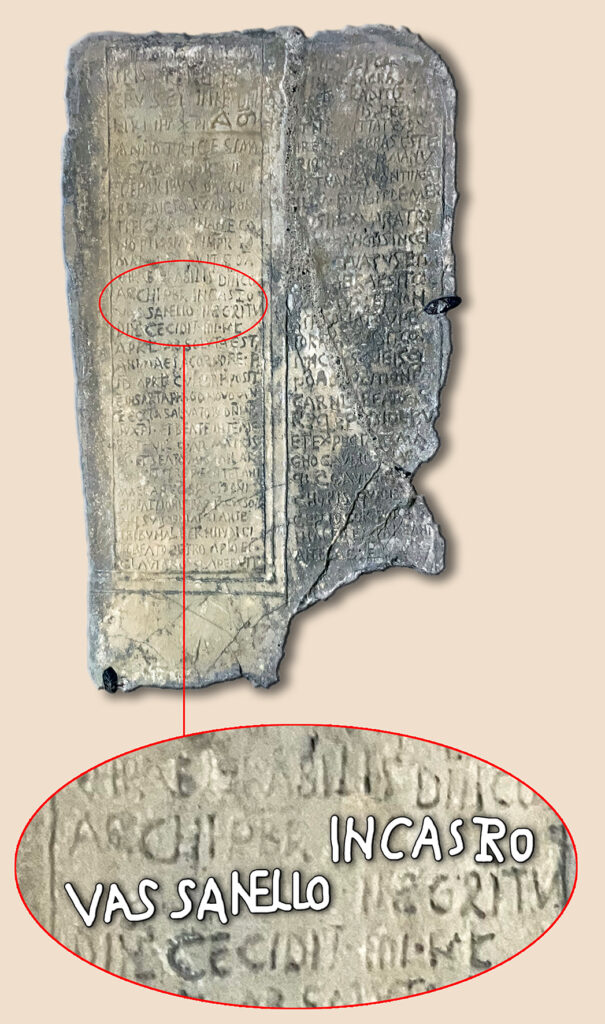

È opinione diffusa che la chiesa risalga all’XI secolo. In effetti questo periodo ben si attaglia all’epigrafe, di cui si è già parlato, riferita ad un arciprete il cui corpo qui venne inumato nel 1038. Non è tuttavia improbabile che, così come proposto dall’architetto Guido Caraffa (“Il restauro della Chiesa di San Salvatore in Bassanello”, Vittorio Ferri Editore, Roma, 1942-XX), la costruzione della chiesa sia piuttosto da ubicare tra la fine dell’VIII e l’inizio del IX secolo. Secondo il Caraffa ciò si dedurrebbe da elementi del tutto simili ad edifici di quel periodo.

Tale ipotesi potrebbe inoltre essere suffragata dal fatto che, nonostante l’uso diffuso delle campane fin dal V secolo, prima del IX non era ancora consuetudine incorporare nelle strutture delle chiese apparati campanari: e infatti il maestoso campanile di scuola laziale, posteriore proprio perché la chiesa ne era originariamente sprovvista, è situato a sé stante.

L’edificio racchiude insomma numerosi elementi di quella architettura ascensionale preparatoria dell’arte romanica, ma che tale non può ancora considerarsi.

Dei loculi scoperti sotto la pavimentazione, e il cippo del VII secolo utilizzato a sostegno della mensa d’altare (forse però proveniente da Palazzolo), fanno supporre che l’edificio sia stato eretto sopra uno preesistente. Elemento decorativo di straordinario spessore artistico è l’affresco della fine del XV secolo attribuito al grande pittore umbro Piermatteo d’Amelia, considerato dallo storico Italo Faldi “uno dei punti più alti che la pittura Viterbese del Quattrocento raggiungesse mai.

It is widely believed that the church dates back to the 11th century. Indeed, this period aligns well with the inscription, previously mentioned, which refers to an archpriest whose body was interred here in 1038. However, it is not unlikely— as proposed by architect Guido Caraffa (The Restoration of the Church of San Salvatore in Bassanello, Vittorio Ferri Editore, Rome, 1942-XX)—that the church was actually built between the late 8th and early 9th centuries. Caraffa’s hypothesis is based on architectural elements remarkably similar to those of buildings from that period.

This theory could also be supported by the fact that, despite the widespread use of bells since the 5th century, it was not yet customary before the 9th century to incorporate bell towers into church structures. Indeed, the imposing bell tower of the Lazio school, which was added later because the church originally lacked one, stands separately from the main building.

The church, therefore, contains numerous features of the transitional architectural style that preceded the Romanesque, yet it cannot be fully classified as such. The discovery of burial niches beneath the floor and a 7th-century funerary stele used as support for the altar table (possibly originating from Palazzolo) suggest that the building was constructed over a pre-existing structure.

A particularly remarkable decorative element is the late 15th-century fresco attributed to the great Umbrian painter Piermatteo d’Amelia. The historian Italo Faldi considered it “one of the highest achievements ever reached by 15th-century Viterbese painting.”